Judul : The whole world is watching our transitional justice process

link : The whole world is watching our transitional justice process

The whole world is watching our transitional justice process

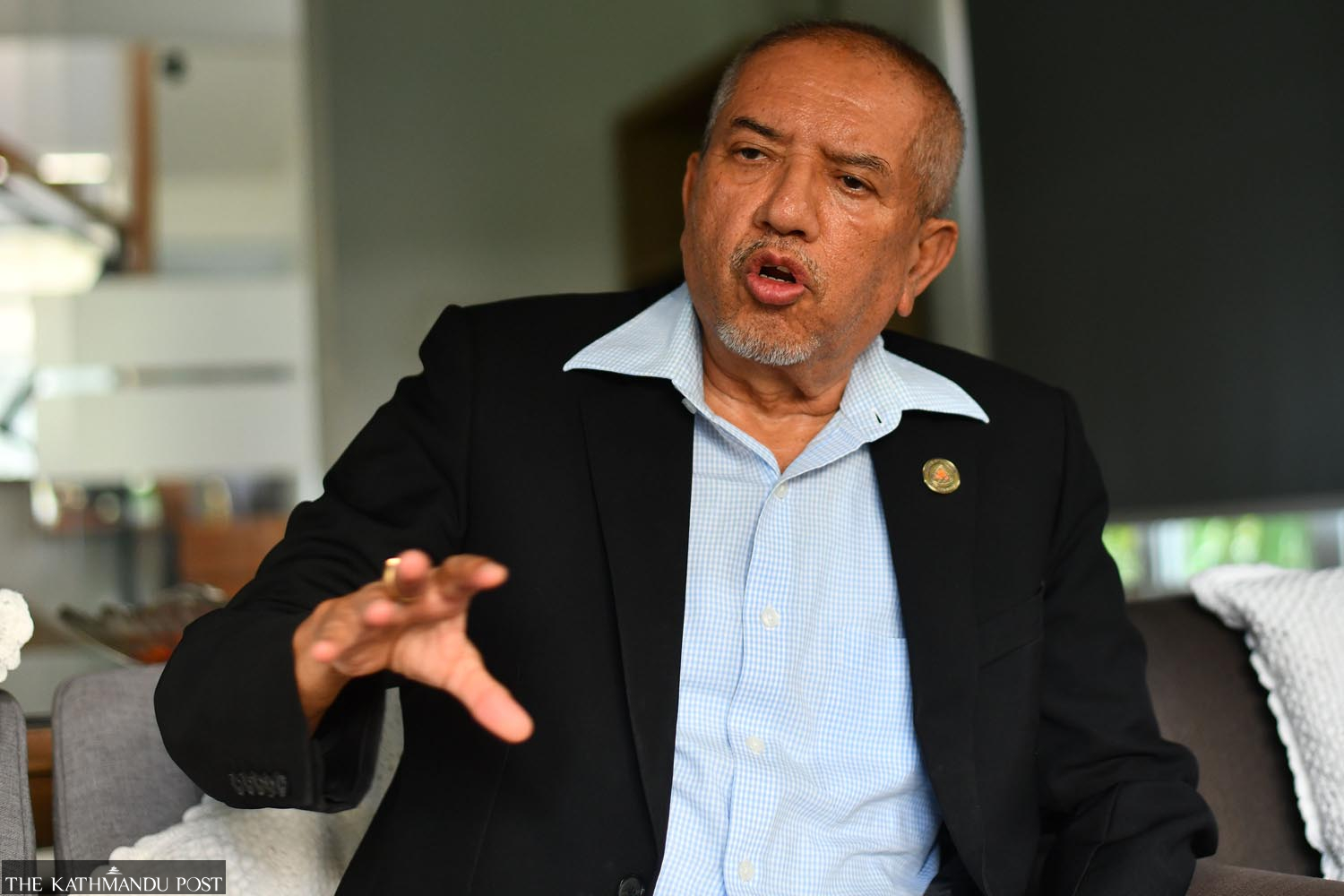

Nepal, July 21 -- The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is not just a human rights watchdog but also a mechanism with a supervisory role in transitional justice. However, it is often criticised for not doing enough in this regard. Binod Ghimire of the Post sat down with Surya Prasad Dhungel, a commission member and an expert in transitional justice, to discuss a range of issues from the constitutional body's performance to the future of the transitional justice process. Incidentally, Dhungel was one of the 52 appointees to various constitutional bodies whose appointments were recently upheld by the Supreme Court.

A recent Supreme Court verdict, which met with widespread criticism, upheld the appointments in several constitutional bodies, including your appointment as an NHRC member. How do you see it as an NHRC commissioner with national and international legal experience?

The Constitutional Council is the highest body responsible for appointments in the country. As such, its composition, procedures, roles and responsibilities must reflect constitutional accountability. The presence of the Speaker of the House and the Leader of the opposition is not optional but a constitutional necessity. There should be no debate on this matter.

Several concerns were raised during the appointment process. The Supreme Court had a wonderful opportunity to provide clear direction on key constitutional questions, but failed to do so-or on time. As Justice Sapana Pradhan Malla rightly observed, how can the court take so long [four and a half years] to deliver a ruling on such an important issue? This delay subjected the appointees to unnecessary criticism for years.

The Constitutional Bench's judgment, passed after four and a half years, was disappointing. The court missed a chance to develop and strengthen constitutional jurisprudence in Nepal. Even as a parliamentary hearing is a mandatory constitutional provision, joint regulation of the federal parliament superseded it. The regulation says the President can make appointments if a hearing cannot take place within 45 days of the recommendation. No regulation can be above the constitution. The court didn't speak on such a vital matter. There were also other such constitutional issues on which the court opted to stay silent.

Did the delay in judgment affect the performance of the commission, and yours personally?

It naturally did. I cannot say all the members were equally affected, but it was in everyone's mind. On several occasions, the chair and members from other commissions expressed concerns about their future. In every review meeting of the NHRC's accreditation, we had to face questions about the court cases against our appointments. However, as the court had refused to issue an interim order as demanded by the petitioners and allowed the commission to function, it indicated that the appointments were legitimate.

While I was still confused about whether to accept the appointment, Anup Raj Sharma, former NHRC chair, told me that I needed to prove through performance that my appointment was justified. I followed his suggestion.

With the appointments upheld, can we see the commission function more effectively from now on?

There was a time when some people from the human rights community would not come to the commission even for interactions, as they opposed our appointment process. The perception of the human rights community, the international community, and even ordinary people towards the commission started to change after it retained its global "A" status last year. Now, with the court verdict, the commission's acceptability has further increased. Those opposing us have started coming for interactions.

If we look at our annual reports, you see that we have expanded our areas of intervention. We are taking up business and human rights issues, working on climate justice and continuously interacting with the conflict victims to advocate for a victim-centric transitional justice process. Our presence at the global forums is very effective.

Likewise, we have taken several measures to tackle human rights issues at the ground level by strengthening our provincial offices. We have also conducted different kinds of research on vulnerable communities, such as the Chepang and senior citizens.

If the commission is working effectively, why isn't its work visible?

Look at the government's attitude towards the commission! Our recommendations go unimplemented, and the government is least interested in providing resources to the commission. We don't have a proper office. It's been years, and the commission is yet to get a long-desired law.

What is stopping you from bringing such issues into the public domain? Why doesn't the commission use its authority to blacklist human rights violators and those who do not implement its recommendations?

It's not that we haven't raised these issues. We raise them strongly in every interaction. After our pressure, a special mechanism was formed in the Prime Minister's Office to facilitate the implementation of our recommendations. A recent Supreme Court ruling categorically said that the commission's recommendations must be implemented unconditionally. In every global forum, Nepal reiterates its full commitment to human rights, but the reality is different.

Climate justice is an important area of the commission's intervention. However, the government doesn't fund our participation in global forums like COP and doesn't commit a penny when we plan an international conference on climate justice. Our staff must travel to rural and remote areas to monitor human rights, but there are no vehicles or resources. Multiple requests to the government have been ignored, so the donor communities have come forward to support us. But the government does not allow us to accept such support. Despite our continuous pressure, the government is reluctant to finalise the bill to reform the NHRC.

The commission is not the executing agency. It is suffering from the government's poor attitude towards it.

As the NHRC holds a supervisory role in transitional justice, how do you respond to the victims' criticism of its inaction as well as of its representative's role in the picking of TJ commission members?

The commission is with conflict victims and human rights communities on transitional justice. In the past, the commission had refused to send its representative to the recommendation committee, presenting the amendment to the transitional committee justice Act as a precondition. The victims and human rights defenders had welcomed the decision. When Manoj Duwady, a member, represented the commission in the committee, the commission missed its deadline to recommend names for the transitional justice bodies. It was also appreciated that the committee didn't succumb to political pressure.

The victims raised questions about the commission's member Lily Thapa being part of the recommendation process. Let me make it clear: The issue was not raised initially, but only after the committee began selection. The entire commission, including Thapa, strongly suggested to Om Prakash Mishra, the committee chair, that recommendations be made after proper consultations with victims.

Even today, the commission clearly states that the recommendations did not follow proper consultations. We have reservations over the selection process, just like the victims.

How do we bring the transitional justice process back on track?

From past experiences, it is clear the commissions that don't have victims' support are doomed. However, who will suffer if the commission fails for the third time-the victims, again? There will be a loss of time, money, and, most importantly, credibility. It will be a national and international shame.

In my opinion, the key is to win the victims' confidence. The two commissions' prime responsibility is to engage with them. In meetings with the victims, the government has been providing assurances, but this doesn't seem to reflect in the actions. It also has a big responsibility to address prevailing grievances. The international community, active during the Act amendment process, also seems silent after the appointment.

What next for the transitional justice process?

Any attempt to press ahead with the process without accommodating the victims' concerns will invite a disaster. It would be against the principle of transitional justice that says not a single victim should be denied justice. The TJ commissions and the government must accommodate victims' grievances. It is not just the victims and human rights activists; the media and civil society should also raise their voices. The international community, which demonstrated so much interest in the TJ process, remains unnaturally silent at this critical juncture. Why?

During a recent meeting with Rory Mungoven, Asia-Pacific Chief of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, I suggested he facilitate victims' visits to other countries to see how similar complexities between victims and commissions were addressed there. Why just the political leadership, the victims also deserve to witness what is happening in other countries.

Failing to address the victims' grievances means the issue will be strongly raised in the United Nations Universal Periodic Review slated for early next year. The government will have to answer before the world.

Are there ways forward for the transitional justice process that we are yet to explore?

This is the nation's problem. There should be no attempt to undermine or ignore the victims. It is the government's responsibility to hear them out and evaluate the options they present. They have been saying the reconstitution of the commission is the only option. Some alternative ways out can be found. But that can only happen through dialogue and negotiations. The constitution of a special advisory committee with representation from the victims, which has the mandate to facilitate the commission, could be an option.

It is pointless to form commissions if victims' concerns are to be sidelined. We should all be mindful that this is not just Nepal's domestic affair; the world is watching.

Demikianlah Artikel The whole world is watching our transitional justice process

Anda sekarang membaca artikel The whole world is watching our transitional justice process dengan alamat link https://www.punyakamu.com/2025/07/the-whole-world-is-watching-our.html

0 Response to "The whole world is watching our transitional justice process"

Post a Comment